In early February, research teams from Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin, München Klinik Schwabing and the Bundeswehr Institute of Microbiology published initial findings describing the efficient transmission of SARS-CoV-2. The researchers’ detailed report on the clinical course and treatment of Germany’s first group of COVID-19 patients has now been published in Nature*. Based on these findings, criteria may now be developed to determine the earliest point at which COVID-19 patients treated in hospitals with limited bed capacity can be safely discharged.

In late January, a group of patients in the Starnberg area near Munich became Germany’s first group of epidemiologically linked cases of COVID-19. Nine patients from this ‘Munich cluster’ subsequently received treatment at München Klinik Schwabing. “At that point time, we really knew very little about the novel coronavirus which we now refer to as SARS-CoV-2,” says one of the study’s lead authors, Prof. Dr. Christian Drosten, Director of the Institute of Virology on Campus Charité Mitte. He adds: “Our decision to study these nine cases very closely throughout the course of their illness resulted in the discovery of many important details about this new virus.”

“The patients treated at our hospital were all young to middle-aged. Their symptoms were generally mild and included flu-like symptoms like cough, fever and a loss of taste and smell,” explains the other lead author, Prof. Dr. Clemens Wendtner, Head of the Department of Infectious Diseases and Tropical Medicine at München Klinik Schwabing, a teaching hospital of LMU Munich. “In terms of scientific significance, our study benefited from the fact that all of the cases were linked to an index case, meaning they were not simply studied based on the presence of certain symptoms. In addition to getting a good picture of how this virus behaves, this also enabled us to gain other important insights, including on viral transmission.”

All nine patients underwent daily testing using both nasopharyngeal (nose and throat) swabs and sputum samples. Testing continued throughout the course of their illness and up to 28 days after the initial onset of symptoms. The researchers also collected stool, blood and urine samples whenever possible or practical. All of the samples collected were then tested for SARS-CoV-2 by two separate laboratories working independently of each other: the Institute of Virology on Campus Charité Mitte in Berlin and the Bundeswehr Institute of Microbiology, an institution which forms part of the German Center for Infection Research (DZIF).

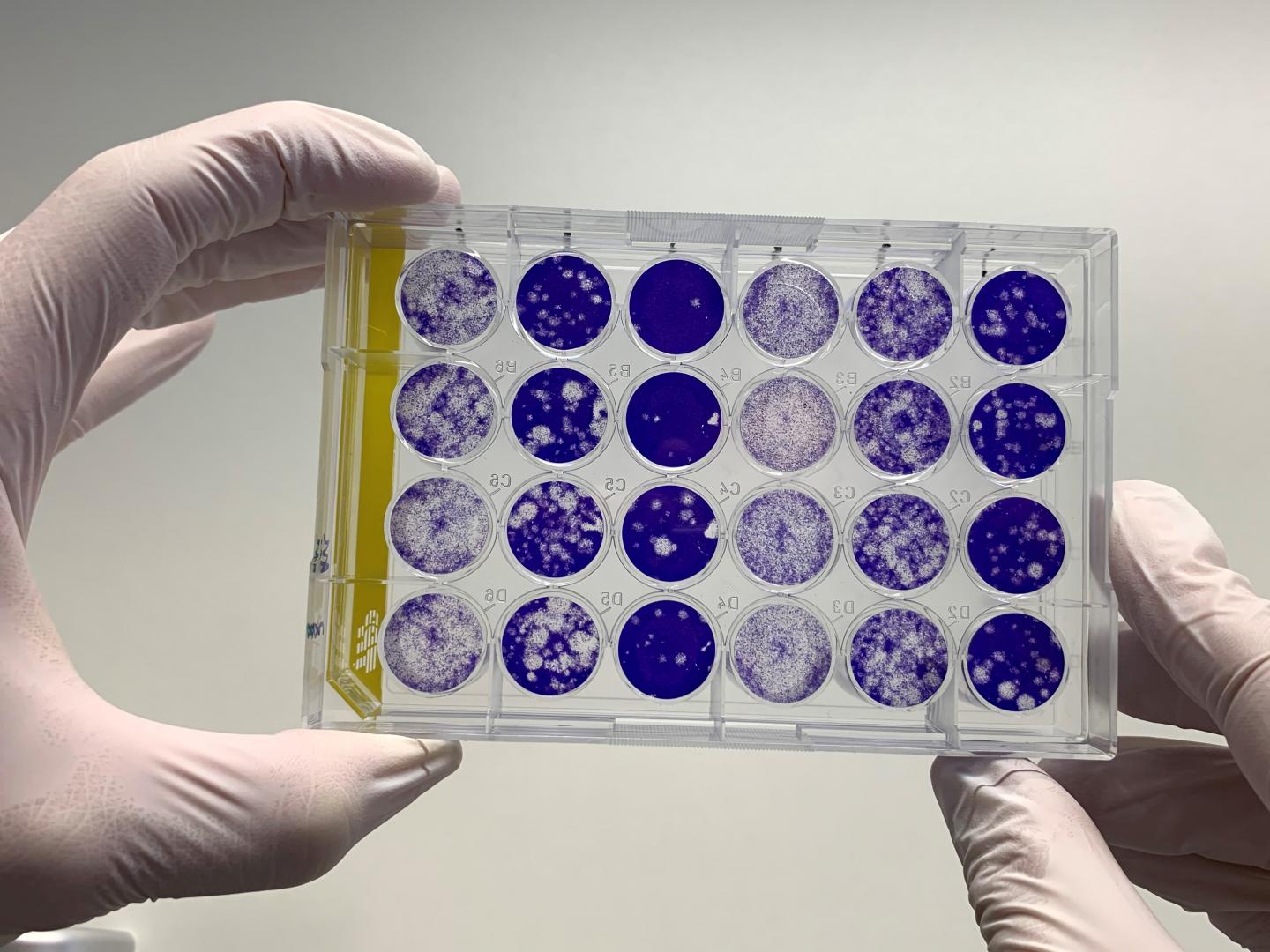

According to the researchers’ observations, all COVID-19 patients showed a high rate of viral replication and shedding in the throat during the first week of symptoms. Sputum samples also showed high levels of viral RNA (genetic information). Infectious viral particles were isolated from both pharyngeal (throat) swabs and sputum samples. “This means that the novel coronavirus does not have to travel to the lungs to replicate. It can replicate while still in the throat, which means it is very easy to transmit,” explains Prof. Drosten, who is also affiliated with the DZIF, and is a professor at the Berlin Institute of Health (BIH). Due to genetic similarities between the new virus and the original SARS virus, the researchers initially assumed that, just like the SARS virus, the novel coronavirus would predominantly target the lungs – thus making human-to-human transmission more difficult. “However, our research involving the Munich cluster showed that the new SARS coronavirus differs quite considerably in terms of its preferential target tissue,” says the virologist, and adds: “Naturally, this has enormous consequences for both viral transmission and spread, which is why we decided to publish our initial findings in early February.”

In most cases, viral load decreased significantly during the first week of symptoms. While viral shedding in the lungs also decreased, this decline happened later than in the throat. The researchers were no longer able to obtain infectious virus particles from day 8 after the initial onset of symptoms. However, levels of viral RNA remained high in both the throat and lungs. The researchers found that samples with fewer than 100,000 copies of viral RNA no longer contained any infectious viral particles. This allowed the researchers to draw two conclusions: “A high viral load in the throat at the very onset of symptoms suggests that individuals with COVID-19 are infectious very early on, potentially before they are even aware of being ill,” explains Colonel PD Dr. Roman Wölfel, Director of the Bundeswehr Institute of Microbiology and one of the study’s first authors. “At the same time, the infectiousness of COVID-19 patients appears to be linked to viral load in the throat and lungs. In hospitals with limited bed capacity and the resultant pressure to expedite patient discharge, this is an important factor when it comes to deciding the earliest point at which a patient can be safely discharged.” Based on these data, the study’s authors suggest that COVID-19 patients with less than 100,000 viral RNA copies in their sputum sample on day 10 of symptoms could be discharged into home-based isolation.

The researchers’ work also suggests that SARS-CoV-2 replicates in the gastrointestinal tract. However, the researchers were unable to isolate any infectious virus from patients’ stool samples. None of the blood and urine samples tested positive for the virus. Serum samples were also tested for antibodies against SARS-CoV-2. Half of the patients tested had developed antibodies by day 7 following symptom onset; antibodies were detected in all patients after two weeks. The onset of antibody production coincided with a gradual decrease in viral load.

The Munich- and Berlin-based research groups plan to conduct additional research on the development of long-term immunity against SARS-CoV-2, both within the first German cluster and in other patients. This type of research will also play an important role in the development of vaccines.